I unintentionally wrote my friend's suicide note, what happened next is incredible...

What follows is the transcript of a speech on military resilience given by Objective Zero co-founder Chris Mercado at South Dakota State University on Tuesday, November 20th.

Justin Miller & Chris Mercado, co-founders of Objective Zero

Thank you for that kind introduction and thank you for inviting me here today to speak. Ladies and gentlemen, distinguished guests, thanks to all of you for sharing your time with me tonight - it’s really great to see some familiar faces out there. I would like to also thank Russ Chavez, SDSU, and the ROTC program here for letting me share my experiences and some lessons learned with their cadets earlier today.

I must begin with a few disclaimers: first, I am here representing myself; this presentation doesn’t reflect the official policy or opinion of the Department of Defense, the US Army, my unit, or the non-profit organization Objective Zero. Errors, omissions, or mistakes are mine alone. Second, some of the topics I’m going to touch upon today are difficult to discuss – trust me, I get that, as I’m sure many of you do as well.

In fact, the official title of this presentation is “Military Resilience.” A more click-bait worthy, but perhaps more accurate title might be, “I unintentionally wrote my friend’s suicide note; what happened next is incredible.”

Today I plan on spending some time talking about, and hopefully dispelling, some of the myths, stereotypes, and stigmas associated with military service, and I also plan on speaking about `military suicide. I will share some of the stories and challenges that I have observed veterans face, and at the end, I hope to offer some suggestions on what individuals, communities, and the military can do to increase their resilience and inoculate themselves against the growing threat.

In 2005 Author and University Professor David Foster Wallace delivered at Kenyon College an extraordinary commencement speech called, “This is Water.” It was subsequently published as a short book and re-popularized in 2013 on social media as a short viral video.

In it, Wallace begins by telling a fish story. It goes something like this:

“There are these two young fish swimming along, and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way who nods at them and says, “Morning boys, How’s the water?” and the two young fish swim on for a bit and eventually one looks over at the other and goes, “what the hell is water?” The point of the fish story is merely that the most obvious important realities are often the ones that are hardest to see and talk about: stated as an English sentence of course this is just a banal platitude. But the fact is that in the day-to-day trenches of adult existence, banal platitudes can have a life or death importance.”

I came across this viral video as it reached its crescendo on Facebook in 2014. A few months later, I started graduate school at Georgetown University. I had just returned from Israel where I was deployed supporting a military mission.

Over the span of a few weeks I noticed that Justin Miller, a former comrade of mine, was posting erratically on social media. My radar went up. I grew increasingly concerned and wondered what I should do.

Justin Miller in Iraq

Justin and I served together in the Army. At the time I was a newly minted lieutenant and Justin a newly minted staff sergeant. We served in different platoons of the same company. We deployed together to Iraq and briefly, in the final weeks of the deployment, I went out on a few missions with Justin and his scout platoon, just to gain some more experience with scout and sniper employment.

In 2014, Justin had recently transitioned out of the military. I knew that the transition could be difficult, but I didn’t know the particulars of Justin’s situation. We weren’t particularly close but I felt that something was seriously wrong.

Seeing that Justin was struggling, I did the only thing I could think of: I called him and asked him point blank if he was thinking of hurting himself. He admitted to me that the night before he was thinking of killing himself, but the only thing that stopped him was that his weapon wasn’t loaded and he was worried that by loading it, he would wake his wife and be forced to explain himself to her.

Hearing that the only reason your friend didn’t point a gun at himself and pull the trigger was because he was worried that the sound of loading it might first wake his wife is shocking to you and I. But David Foster Wallace wrote something that I think will help us put suicide into perspective:

"The so-called ‘psychotically depressed’ person who tries to kill herself doesn’t do so out of quote ‘hopelessness’ or any abstract conviction that life’s assets and debits do not square. And surely not because death seems suddenly appealing. The person in whom Its invisible agony reaches a certain unendurable level will kill herself the same way a trapped person will eventually jump from the window of a burning high-rise. Make no mistake about people who leap from burning windows. Their terror of falling from a great height is still just as great as it would be for you or me standing speculatively at the same window just checking out the view; i.e. the fear of falling remains a constant. The variable here is the other terror, the fire’s flames: when the flames get close enough, falling to death becomes the slightly less terrible of two terrors. It’s not desiring the fall; it’s terror of the flames. And yet nobody down on the sidewalk, looking up and yelling ‘Don’t!’ and ‘Hang on!’, can understand the jump. Not really. You’d have to have personally been trapped and felt flames to really understand a terror way beyond falling."

This helped me to understand what Justin was going through. It wasn’t that death seemed appealing to Justin; suicide was simply the less terrifying of two terrors. He was embarrassed with serious drug and alcohol addiction, was suffering from the physical and mental traumas he experienced at war, was unemployed, and was struggling to navigate the bureaucracy of the VA’s healthcare system.

“This past summer, in San Francisco, Justin and I were telling the backstory of a non-profit organization we helped co-found to some tech-savvy mentors. As we were reflecting on his story, Justin said to me for the first time that the story he let me publish, his story, was actually intended to be his suicide note. Justin revealed that he wanted the world to know why he took his own life. ”

I stayed on the phone with Justin for over six hours. His story was incredibly powerful and simply telling it to me it proved cathartic for Justin. At the end of the call I asked if he was still thinking of hurting himself. His answer, “No – I feel great, I just wanted someone to talk to and listen to me.”

Knowing that Justin isn’t alone in his experience, and that his story might inspire others to seek help, I convinced him to let me interview him and publish a short article based on his life and his experiences. Though Justin agreed, he drug his feet on the interview. Weeks later, Justin finally caved in and let me dig deep, asking all the really difficult, penetrating questions to share openly with anyone who would listen.

And listen they did. Justin Miller’s story has been downloaded and read thousands of times on Medium.com. Justin has been interviewed for dozens of articles and has made appearances on multiple podcasts and has even been interviewed on CNN.

This past summer, in San Francisco, Justin and I were telling the backstory of a non-profit organization we helped co-found to some tech-savvy mentors. As we were reflecting on his story, Justin said to me for the first time that the story he let me publish, his story, was actually intended to be his suicide note. Justin revealed that he wanted the world to know why he took his own life.

It was the overwhelming response Justin received, the dozens of calls and emails from veterans praising him for his courage, thanking him for his inspiring message, and asking him for help that kept him going. Justin had found new purpose in his life.

Justin Miller isn’t alone in his experience.

Recently, I have been helping one of my former Soldiers, Sergeant James Ingle, with his recent transition out of the military. James also served in Justin Miller’s unit. To say that James is struggling is an understatement. James allowed me to share his story here with you to put some of the challenges our veterans face into context:

On March 13th, 2007, James and his platoon left Forward Operating Base Falcon, southwest of Baghdad, en route to Muhallah 822 of Dora district. At the time Dora district was one of the most dangerous hotbeds of the insurgency in Iraq. During their fifteen month deployment to Baghdad, 18 Soldiers of James’ and Justin’s unit would pay the ultimate sacrifice.

When his platoon left their operating base, James’ vehicle led the convoy to their destination. During the mission, James’ truck suffered from mechanical difficulties, and the mission commander changed the platoon’s order of movement for its return trip to FOB Falcon. As the patrol was leaving Muhallah 822, the lead vehicle erupted into flames as it was struck by a roadside bomb.

“I watched the explosion,” James recently told me on a phone call. “I observed the medics insert the FAST1 sternal intraosseus infusion to try and save my friend’s life. I was with Doc Boller as SGT Carr took his last breath.”

James went on to say, “It was supposed to be me. That was my day.”

Three months later, James was a machine gunner perched atop a HMMWV as his platoon was responding to an event that occurred after insurgents daisy-chained a string of homemade explosives to a massive deep-buried IED. The detonation of these explosives resulted in a mass casualty event, and James’ unit was among the first responders.

Sitting at a T-intersection James observed a white car pull up to the left of his gun truck. James rotated his machine gun turret to orient on the car and, after repeated verbal and visual warnings, the car sped away. As James re-oriented his weapon down the road he realized the car had merely been a distraction:

“I saw a guy coming at me holding a large bag that looked like a purse,” James said. “He threw it and it landed on my HMMWV. After it exploded I fell through the turret and hit my head on the radio and lost consciousness.”

Like many, James never fully let go of the shock and trauma of his experiences in combat. He self-medicated through alcohol. He struggled with depression. After his most recent deployment to the Arghandab River Valley near Kandahar in Afghanistan, James drank a 12 pack of Michelob and, sitting with a loaded pistol, contemplated why he survived when others like his friend SGT Robert Carr had not.

The next day he went to his Chain of Command to seek help. His Command Sergeant Major did something simple, but amazing. He took James fishing. And just listened to him.

“That’s what saved me.” James later said.

James reached out to me a few months ago as he was rebutting the Physical Evaluation Board that would involuntarily separate him from service and medically retire him. He had once again hit rock bottom.

After 13 years of service and deployments to Iraq and to Afghanistan, James was medically retired from the service. He has struggled with migraines since the explosion that resulted in his service-connected Traumatic Brain Injury. He has COPD, a disease that causes obstructed airflow from the lungs, linked to his exposure to burn-pits in Afghanistan. He has also been diagnosed with anxiety disorder with depression. Since his separation from the military, James struggled finding employment and his wife nearly left him.

Since James and I reconnected I have spent hours with him on the phone listening to his experiences, I have helped him to stop self-medicating with alcohol, and perhaps most importantly, I helped him find employment.

What Justin and James experienced is not uncommon among our service-members and our veterans. It is also reflective of our society at large.

Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in our society and results in nearly 45,000 total deaths per year – both military and civilian. According to the National Institute for Mental Health, in 2016 suicide was the second leading cause of death in people aged 10-34. In fact, there were twice as many deaths by suicide as there were deaths by homicide in that same year.

This is especially hard on our military community. In its recent suicide data report, the VA noted that on average 20 veterans and active duty service-members die by suicide every single day. This is a rate that is twice that of the non-veteran population. Female veterans are especially vulnerable, dying by suicide at a rate that is 2.5 times as likely as their civilian counterparts.

While the number of active duty service-members dying by suicide doesn’t seem like a large number it actually is quite alarming. Actively serving members of the military constitute less than ½ of 1 percent of all Americans. Put into perspective, I am an infantry officer. This rate of suicide in the active duty forces constitutes a platoon of Infantrymen dying every month, a company of infantrymen dying nearly every quarter, and nearly a battalion of infantrymen dying every year.

But this rate of suicides doesn’t pose an existential crisis for the military or our society. It is a slow death by a thousand cuts; gradually sapping the readiness of our active force and exhausting the empathy of leaders tasked with training our Soldiers to deploy, fight, and win our nation’s wars. It is unsurprising to hear military leaders say that suicide is a selfish act and that those who struggle with depression are simply physically and mentally weak. This is understandable not because they actually believe these things, but because they do care tremendously about their Soldiers and are emotionally frustrated that they haven’t found a solution to the problem. Put simply, if it were easy, we would have solved this problem already.

What these leaders are experiencing are the compounding effects of cognitive bias and compassion fatigue. In fact, there are a number of stereotypes, stigmas, and myths surrounding military service that are working against our service-members and veterans – all of which pose barriers to care.

One of the first stereotypes, and frankly one of the most damaging to our veterans, is that all of our service-members come home from war broken and angry. In fact, nothing could be further from the truth – the reality is that none of our veterans are ‘broken.’ Some of our veterans are struggling, like Justin Miller and James Ingle. They may be struggling with addiction, physical or mental injuries, access to education or employment – but none of them are broken. The reality is that the overwhelming majority of our veterans leave the military with a wealth of leadership expertise, technical skill, and real-world experience – all of which they infuse into their communities, enriching them and lifting them up.

Another stereotype, one that poses a significant barrier to care for veterans, is that the VA is failing to provide adequate care for our warfighters. Again, this is a really pervasive and damaging stereotype. While it is true that some veterans have bad experiences with the VA, the overwhelming number are receiving excellent care from the VA. In fact, the VA is providing health care, vocational rehabilitation, education benefits, and other services to over 8 million veterans at more than 1,700 locations. At over $182 billion, the VA’s budget request for 2017 rivals that of the entire defense budget of China. What is noteworthy, however, is that the data shows that veterans enrolled in VA healthcare are at a substantially lower risk of self-harm. Despite this, the VA only has approximately one-third of America’s veterans enrolled. This stereotype puts a bias in the minds of veterans; if a veteran does have a sub-standard experience, it confirms all the bad news stories – despite having had a prior record of good experiences.

A third stereotype, one that makes it difficult for service-members and veterans to seek help, is that only those who “fought” on the ground “understand” the psychological costs of war, the emotional trauma of combat, or the rigor of military service. This presumes that only close physical proximity to danger qualifies as “combat experience” and marginalizes those experience of war involves the remote targeting of enemies and those who weren’t on the front lines. It also excludes those who suffer from moral injuries and victims of military sexual trauma. The reality, though, is that for the last 17 years of war, there has been no such thing as a “front line” of combat. A supply clerk on a large forward operating base is every bit as vulnerable to incoming mortar or rocket fire as an infantryman or cavalryman taking direct fire from the enemy. In fact, data suggests that there is no meaningful correlation between combat service and suicide and points instead toward weak social connectedness as a more likely culprit. What is particularly sad about this stereotype is that it trivializes the experience of our warfighters – and often times – it is perpetuated by those in the combat arms themselves.

These harmful stereotypes are compounded by some of the stigmas we already experience in the military. Speaking from my own experience, I can say that there remains a bias against seeking help in the military – whether that’s help for a physical or a mental injury. Carrying your share of the load is an important concern in the military, and no one in the military wants to be perceived as weak. Even though leaders in the military have worked hard to combat this stereotype, it does still exist. Combating this stigma is the most important thing leaders in the military can do to reduce suicide in the ranks.

“The reality, as David Foster Wallace taught us, is that suicide has a“seductive logic”: it’s about ending pain. Death is seen as an answer to a problem. It is the lesser of two terrors. ”

And because of the stigma, seeking help is often seen as scarier than death.

David Foster Wallace would know. For over 20 years Wallace himself struggled with a major depressive disorder and, on September 12th, 2008, he died by suicide.

The cumulative effects of fear, danger, uncertainty, and combat trauma lead to breakdowns of self-discipline and erode unit cohesion. They weaken our resolve and test our resilience. They limit our ability to make and maintain meaningful relationships and, particularly when we leave the military, result in a loss of meaningful purpose.

What can be done?

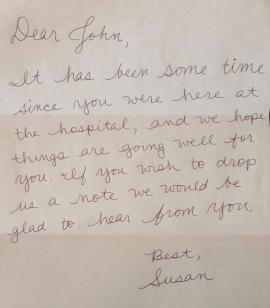

Psychiatrist and suicide researcher Jerome Motto, himself a veteran of WWII, offers a simple, but powerfully effective way of countering the downward spiral to suicide. Inspired by his own experience in WWII receiving letters from home, Motto believed that the simple act of connecting could dramatically reduce suicides. After the war, Motto attended Berkeley where he studied psychology and later completed medical school at UC San Fransisco. In 1965 he came upon the writing of Hellmuth Kaiser, a German psychoanalyst, who wrote that patients who felt a sense of connection, of belonging, can help people the most.

This prompted Motto to undertake a research study that tracked suicidal patients that had been discharged from San Fransisco’s psychiatric facilities. Motto’s study randomly divided subjects into two groups: a control that received no further contact and another group that received continuous contact through simple form letters.

The content of the letters was simple, but genuine. One letter said, “This is just a note to assure you of our continuing interest in how you are getting along.” Another wrote simply, “Just a note to say that we hope things are going well, as we remain interested in your well being. Drop us a line anytime you like.”

In each of these letters, Motto’s research team enclosed a self-addressed return envelope to encourage recipients to respond. Over the five years between 1969 and 1974 Motto’s team connected with over 3,000 patients.

The results of Motto’s study were absolutely stunning: in the first two years following hospitalization, the suicide rate of the control group (that received no further communication from Motto’s team) was nearly twice as high as that of the group that received continuous contact and connection.

There wasn’t anything special about Motto’s letters to his research subjects. They were simple, heartfelt, and genuine, not unlike David Foster Wallace’s message in his fish story, “How’s the water boys?” The simple act of listening, and connecting, had a profound impact on their lives.

What I’ve found is that sometimes, as in Justin Miller’s case, there are obvious signs or symptoms that someone is struggling. These signs may include talking about suicide, an increased use of alcohol or drugs, withdrawing from social contact or isolation, and most importantly – access to lethal means like firearms.

What I’ve also heard frequently from family members after a suicide is that they saw no symptoms – they didn’t see any changes in behavior or patterns of life. This is why it’s important for everyone in a community to pay attention: people are willing to dismiss a single sign or symptom as an isolated event – but they might be missing the larger picture.

If you see these signs or symptoms, it’s extremely important to intervene – to act – to reach out, but remember, if you think that someone is imminently in danger, it’s never wrong to reach out to the experts: never be afraid to call 911 or the national suicide prevention line. (1-800-273-8255).

In May of 2016, shortly before my own graduation from Georgetown, I was asked by my Uncle Henry to give a speech on Memorial Day in Sioux Falls. In it I did something I do very rarely: tell my own stories. Now and again I let some of my stories slip; in other cases, it is my former Soldiers, NCOs, and officers who tell stories about me. Initially upon hearing some of these stories, I’m sure my wife was shocked. Now I’m certain she’s desensitized as to how cavalier I have been with my own life and just takes comfort in the knowledge that I’m good at what I do and will always do what is necessary to come home safe.

But there’s a reason I don’t share my stories with other people. It’s not that I don’t have many interesting, humorous, or even horrible war stories. And it has nothing to do with humility or modesty. I have, as many veterans do, compartmentalized them. Compartmentalizing those stories, the good ones and the bad, gives me a sort of peace of mind; I no longer need to confront some of the horrible things I saw at war. Unfortunately, some of the beautiful and wonderful things I experienced become casualties as a result. Compartmentalizing the bad things has worked for me; it is not something I recommend for others, and frankly, it probably isn’t healthy at all.

Instead of telling my own stories, I prefer to tell the stories of others. To share the stories of veterans like Justin Miller and James Ingle. Powerful stories of really fantastic people who have struggled, and who continue to struggle, but have survived suicide.

“Somebody has to speak for those who are not so strong, who are fearful, who are discouraged, who are distrustful of helpers, who are despairing, who are timid,” said Jerome Motto. ”

Too many people, in uniform and out, are suffering in silence. Whether or not you’ve ever served in the military, if you’re struggling, don’t suffer in silence. Reach out. You’re too important not to.

For the rest of us, you may be wondering: what can you do? What can communities do? I believe, as Motto did, that the simple act of listening, of genuinely caring, and reaching out, can have a tremendous impact on the lives of others.

While on the one hand we found that while the decision to take one’s own life is intensely personal and the reasons or cumulative reasons are too varied to be exhaustive, there were two factors in particular that really persisted across many of the stories of veteran suicide we encountered. They are as Viktor Frankl noted: a loss of meaningful purpose and loss of meaningful relationships.

When someone like Justin Miller or James Ingle join the military, for whatever reasons they initially join, they become part of a team, a family, that literally counts on them for their survival. They also contribute to something much more important than themselves – they have a sense of purpose, of mission, and meaning. When veterans leave the service, they sometimes lose this sense of meaningful purpose and they lose the powerful and meaningful relationships they built in uniform. They literally lose the connection to their community.

For our veterans who’ve transitioned out of the military, it is as David Foster Wallace said, “The constant gnawing sense of having had, and lost, some infinite thing.”

I submit that perhaps the best solution lies not within us, as individuals, but within our communities. We are stronger together and the power of the human connection cannot be overstated. I encourage all of you to embrace those important in your lives, including our veterans. We would do well to follow Wallace’s guidance: to replace irony with sincerity; cynicism with earnest sentimentality; and a sincere yearning for meaning and human connection.

For all of you older fish out there, swimming around in our everyday fishbowls, please remember that the banal platitudes really do matter. Jerome Motto’s simple, but heartfelt and genuine messages may make all the difference. When you come across a couple younger fish, don’t hesitate to reach out, to connect, and say, “Hey boys, how’s the water?” It might just be the difference between life, and death. For all of you little fish out there struggling in the trenches of day-to-day adult existence just remember: this is just water.

Photo found here

Thank you for sharing your time with me today. Have a Happy Thanksgiving and Happy Holidays!